During that winter of 1777 when George Washington and his troops made their winter camp at Valley Forge, the Continental Army faced some of its worst conditions. The Oneida came to aid their American allies. Yet, over the years, that kindness has all but vanished from mainstream American History.

When a harsh winter set in, it became harder for the army’s supply system to get goods to the soldiers. They were starving and had inadequate supplies and clothing. It was even noted that the soldiers’ feet would bleed due to their feet freezing in their boots, which served little protection.

Tribal Historian Loretta Metoxen, wrote “Chief Shenandoah (the deer) was an unwavering friend to the Americans. He believed in the cause of the Colonist and warned his white neighbors of British invaders. It was he and his Oneidas who saved Washington’s starving army at Valley Forge by bringing them several hundred bushels of corn.”

Several hundreds of bushels would convert into seventy pounds per bushel and the route was no easy one. The Oneidas traveled over two hundred miles from Fort Stanwix to Valley Forge. Even with this amount of corn, it was not enough to adequately feed all the troops, but this was considered a great deed by the Oneidas. The corn they brought was white corn and different from the yellow version that is prepared simply. By contrast, the white corn required extended preparation before it could be eaten. The soldiers, however, were desperate for food when the Oneidas arrived, and they tried to eat the corn uncooked. The Oneidas stopped the soldiers, knowing that if they ate the raw corn, it would swell in their stomachs and kill them.

According to Oneida oral tradition, an Oneida woman named Polly Cooper walked several hundred miles from her home in Central New York to Valley Forge in the cruel winter of 1777–78 to help feed Gen. George Washington’s starving troops. She had stayed with the troops and taught the soldiers how to cook the white corn, taking them through the preparation process and the lengthy cooking time. She stayed on after the other Oneidas departed for their homeland and continued to help the troops.

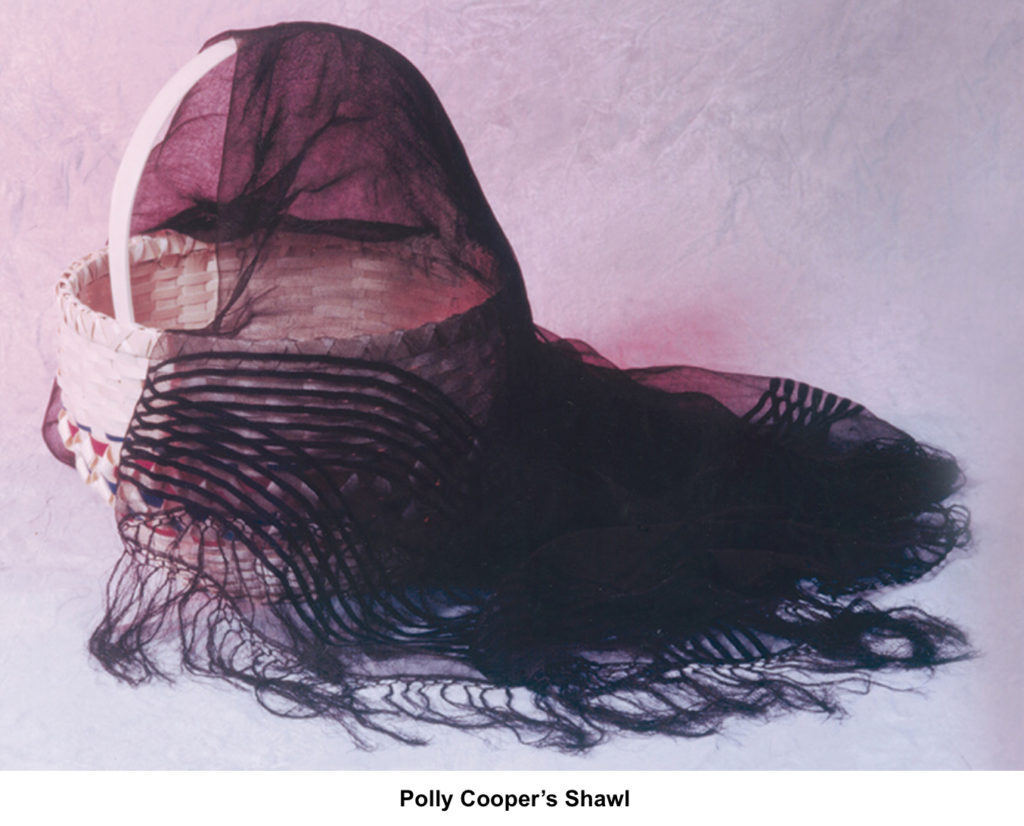

There are two different accounts of how she was recognized. In one story, Washington had offered her money, but she refused. Martha Washington had bought her a shawl, bonnet and hat from Philadelphia. What is known is that Martha gave Polly one of her shawls.

After the war, the Colonial Army tried to pay Polly Cooper for her valiant service, but she refused any recompense, stating that it was her duty to help her friends in their time of need. However, she did accept the token of appreciation offered by Martha Washington. The shawl has been handed down by successive descendants of Polly Cooper.

The United States Congress in 1777 recognized the Oneida contribution to the Revolutionary War stating: “We have experienced your love, strong as the oak, and your fidelity, unchangeable as truth. You have kept fast hold of the ancient covenant-chain, and preserved it free from rust and decay, and bright as silver. Like brave men, for glory you despised danger; you stood forth, in the cause of your friends, and ventured your lives in our battles. While the sun and moon continue to give light to the world, we shall love and respect you. As our trusty friends, we shall protect you; and shall at all times consider your welfare as our own.”

TEXT SOURCE: Upper Merion Township – The First 300 Years by J. Michael Morrison, Francis X. Luther & Marianne K. Hooper