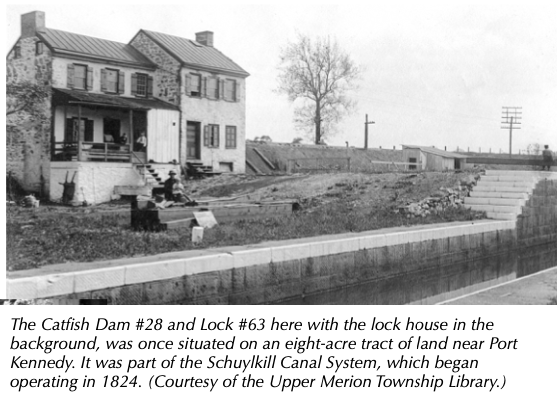

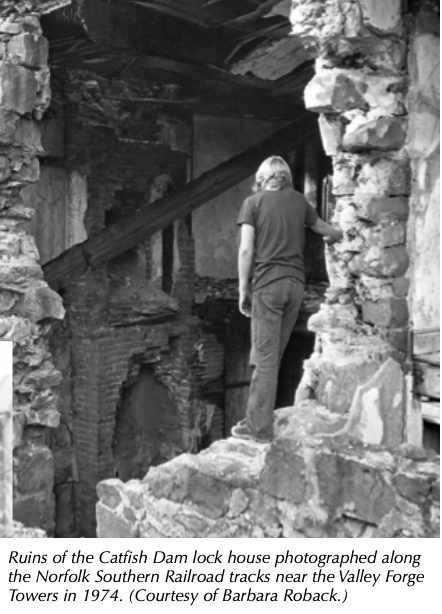

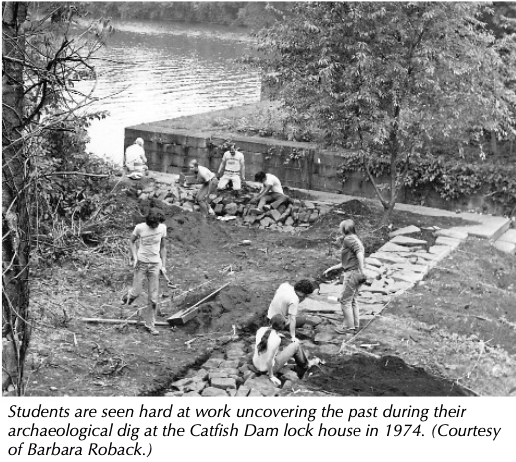

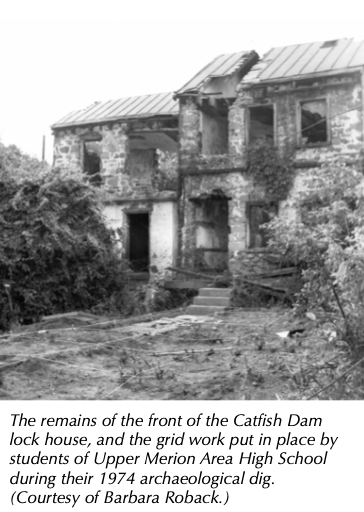

During a summer Anthropology course at Upper Merion Area High School in 1974, the history of the Catfish Dam Locks was studied and included an archeological dig at the site. Here is the report and a few pictures on students’ findings.

On October 23, 1824, one hundred and five “arks” and eight boats filled with forty thousand bushels of coal were waiting above an uncompleted, drained portion of the canal. The porous limestone bottom, within three quarters of a mile of the Reading Railroad tracks, had caused leaks in the canal bed. On November 6, water was reintroduced to the area, but it all leaked out through the limestone in a matter of minutes. The engineers announced a two-week delay and went back to work. The New York Company, which owned the boats, had them hauled two miles across land to outlet locks.

By 1825, most navigation difficulties were overcome and a boat completed the entire voyage. It had been built either at Orwigsburg or Schaefferstown and was escorted to the water by a crowd. The first trips took three to four weeks, but with the addition of horses, the time was reduced to ten or eleven days. From April 16 to 24, 1826, sixty-five boats passed through the Bridgeport locks: sixty-two freight and three passenger. In 1830, eighty-one thousand tons of coal were conveyed by boat in the canal. The Schuylkill Canal’s primary function was the transport of anthracite coal from the mines to the growing industries around Philadelphia, Reading, Pottstown, Bridgeport and Conshohocken. The pastoral banks of the lower Schuylkill were greatly changed to a busy, bustling coal market as a result.

The Schuylkill Navigation Company prospered because of its monopoly and ability to change. The canal was originally three feet deep and accommodated twenty-five tons, but as time went on, it was deepened, allowing for heavier boats. The first considerable enlargement of the canal occurred around 1834, when the depth of the water was increased to five feet. It was forty feet wide at the surface, twenty-five at the bottom. Boats now held one hundred and eighty tons; eventually the weight went as high as two hundred and seventy tons. Newer and higher dams were built and eight locks were doubled to allow boats to pass both ways simultaneously. The dimensions of the locks, originally required to be 20 by 120 feet, were altered by the Act of February 8, 1816 to not less than seventeen by eighty and the number of locks were reduced from one hundred and nine to seventy-two.

Steamboats could not be used on the canal because the churning of the water destroyed the canal walls. However, as early as 1921, a sixty-five foot steamboat, using what locks had been constructed, traveled from Philadelphia to Norristown.

A drought in 1825 ceased navigation for the summer and the Catfish Dam was rebuilt. The canal could not be used in the winter, as the river could, because the still water would freeze. Coaches and wagons were used as alternate transportation. The stagnant water was held responsible for a fever that spread along the canal in the 1820’s.”

Three miles of the canal bed had to be riprapped (paved) with limestone to lessen the seepage. The stone may have come from nearby Reeseville, now King of Prussia in Upper Merion Township, which had one of the best deposits in the country.

With the opening of the Philadelphia and Reading Rail- road in 1842, the canal system’s previous monopoly on anthracite transport was broken. Still, the canal system was cheaper than the railroads for heavy iron and coal shipments. The toll from Philadelphia was twelve cents per one hundred weight.

Passengers paid an eighty-seven cent fare. There were three round-trips every week between Philadelphia and Norristown. Pulled by horses at five miles per

hour, the boats left Norristown at two p.m. and arrived at Philadelphia in the evening. Other passenger boats left Reading at five 5a.m. each Sunday and Wednesday. There was lodging for the night at Pawlings Bridge – many boatmen tied up at locks overnight – with arrival in Philadelphia at eleven a.m. The fare was $12.50, and presumably included room and board.

There were floods on July 19, 1850 and May 21, 1894, but the biggest flood, on September 2, 1850, did considerable damage to canal banks, locks, and lock houses. Tumbling Run reservoir was destroyed and twenty-three dams were damaged. Two dams, including the Blue Mountain Dam, had to be rebuilt entirely. J.F. Smith became Chief Engineer of the canal that year. He was succeeded in 1876 by his assistant and son, E.P. Smith, who worked until 1912.