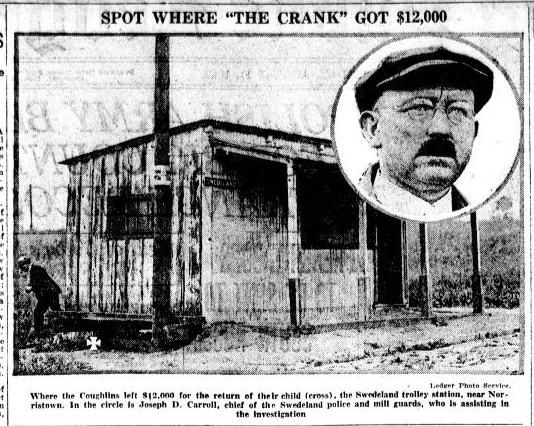

The Swedeland trolley station was that ‘spot where “the crank” got $12,000’ back in 1920. Read more about the famous “Coughlin Kidnapping” case in this 8/27/15 post by the Montgomery County Historical Society:

A few weeks ago, HSMC [and King of Prussia Historical Society] member James Brazel was in the headquarters doing some research in our microfilm collection, when he came across one of Montgomery County’s most notorious crimes: the kidnapping of baby Blakely Coughlin from his family’s home in Plymouth Township.

Thirteen month old Blakely was kidnapped from his nursery at 2 am on June 2, 1920. The kidnapper was an Italian immigrant named Augustus Pasquale (spelled Pascal in the early reports) who got the idea one night when he saw the family through their window while he was walking to the train. Pasquale took a ladder from a nearby house, climbed through the window and took the baby from his crib. He buttoned the baby up in his coat as he went from the house, and after a little while he discovered that he had smothered the child. He then went to the Schuylkill, tied the small body to a piece of iron, and put both in the river.

Then he sent several demands for ransom to the Coughlin family signing them, “The Crank.” Though the family was not very wealthy, the boy’s father, George H. Coughlin, managed to raise $12000. He left the money at a trolley station in Swedeland. When the baby was not returned the state police, under Lynn Adams, stepped in. It was by agreeing to pay another $10000 ransom, that the police managed to trap Pasquale. This time, Coughlin was instructed to throw the money from an Atlantic City bound train when he saw a white flag waving along the tracks. Adams had lined the tracks with state police, and when Pasquale appeared to retrieve the bag, he was arrested. He later confessed and plead guilty to second degree murder, kidnapping, and extortion. Since Blakely Coughlin’s body was never recovered, first degree murder charges could not be brought, and Pasquale escaped the death penalty.

And that’s certainly an interesting story. But I wanted to know more, so I went to our microfilms of the Times-Herald to follow the case in “real time.” Day after day through the month of June and into July, the Times-Herald covered the story. Theories about the case abounded in the early days, with the newspaper reporters asserting that the kidnappers must be a man and a woman based on some footprints. The county commissioners offered a reward for the return of the baby.

Various suspects were brought in, questioned, and released. There were at least a half dozen sightings of babies, in Pittsburgh, New York, and as far away as Arkansas. The Herald blamed police for not doing enough and conducted it’s own investigation. In the 1940’s and 1950’s, Pasquale repeatedly applied for parole, citing his age and poor health. He also changed his story, often in ways that matched the early reports. He claimed to have had accomplices, one a former servant of the family. Later he said he kidnapped the baby with a woman who was desperate for her own baby. Other times he claimed to be completely innocent.

In 1957, Pasquale, nearly blind and suffering from cancer, was released, but he soon violated his parole by leaving the state. He said he had gone in search of the other people involved in the kidnapping. After he was arrested, but before he confessed, Pasquale had also claimed to have accomplices.

Reading through the day to day details of the case, helps me to experience the events, the way someone in 1920 experienced them. All the details and the false leads because part of the story, too. The sweetest and saddest parts, of course, were the quotes from Blakely’s parents. His father was asked to describe him in the very first article: “He was a husky boy of thirteen months. He had blue eyes and a fat round face and light hair.”

https://hsmcpa.wordpress.com/…/…/27/the-coughlin-kidnapping/